On 12 February, Cal Revely-Calder began his critique of the current state of Beckett studies by allowing readers of the Times Literary Supplement to drop their jaws at the bad behaviour that can go on at academic conferences. The essay made its revelation broadly in the name of ‘care’ – care for the work of an author who is apparently being ill served by a particular scholarly community, and care for the way ‘power’ comes to distort the writing and relationships produced by that field. The Samuel Beckett Society shares Revely-Calder’s concerns about care and power in scholarly communities, but we disagree with his account of our field and prescriptions for how it might be saved from itself. We were also surprised that neither the author nor the TLS took care to ensure that crucial details of the anecdote chosen to open the article were correct.

The essay argues that Beckett studies is dominated by genetic manuscript studies in ways that carelessly push out other voices. It is true that the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project has increased access and therefore the scholarly attention given to Beckett’s writing methods and intertextual influences. Researchers from around the globe are no longer obliged to get on a plane to Austin or Reading to access these documents. Those of us currently in lockdown, or with individual circumstances that have always made such trips impossible, feel particularly grateful for this resource. Most of our community are not genetic manuscript scholars; nevertheless, almost all of the diverse ways of thinking in Beckett studies have benefitted from the careful work of the BDMP. Many of us also use this resource in our teaching and we note, with pleasure, the excitement students often experience when they suddenly feel close to Beckett’s writing hand. It is our job, as scholars and teachers, to help them understand what they might make of the strange braiding of proximity and distance, of knowing and not knowing, that is characteristic of Beckett’s writing and is in no way unknotted by having digital access to annotated manuscripts.

Beckett studies has always understood itself to be in dialogue with readers, writers and creative practitioners who sit beyond the academy. Recently, the performer Jess Thom spoke of how her extraordinary Touretteshero production of Beckett’s Not I, which insisted on the primacy of disabled experience and the political value of ‘relaxed performance’, was significantly enabled by Beckett scholars. It helped, she said, to learn about Beckett’s longstanding interest in disabled language; it helped, she said, to feel secure in the terms she found to approach the protective Beckett Estate and gain their trust and support. Partly because the appetite for staging Beckett remains so strong, encounters with his work in the world beyond academia are frequent. Over the last year, Beckett has been appealed to in journalism perhaps more than any other literary author. Whether we are waiting for Godot, stuck inside in a ‘refuge’ with family whom we might sometimes rather discard, or clinging to daily routines as catastrophes accumulate around us, Beckett has been refound as the laureate of lockdown. During the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, it was a ‘blues line of our Irish brother’, Samuel Beckett, that Dr Cornel West decided to quote to CNN’s Anderson Cooper. If Beckett studies imagines itself to be policing encounters with the author’s work, it is doing a poor job.

Revely-Calder is concerned that the scholarly field, as it stands, writes out its ‘more interesting’ voices. The essay enjoins Beckett studies to ‘have a good look at [it]self’ and come to the chastened realisation that ‘All ethics is grounded in self-scrutiny, in thinking again on how we form judgments and put them into words’. Again, there is a suggestion of insufficient care. But it is odd that the essay’s concern with the stylistic qualities of other people’s sentences, which are variously described as ‘dire’, ‘windy’, ‘baggy’ or full of ‘hot air’, is not paired with a reflection on how or why particular judgments about style are formed, or how and why some voices and styles have historically found themselves so effortlessly raised above others.

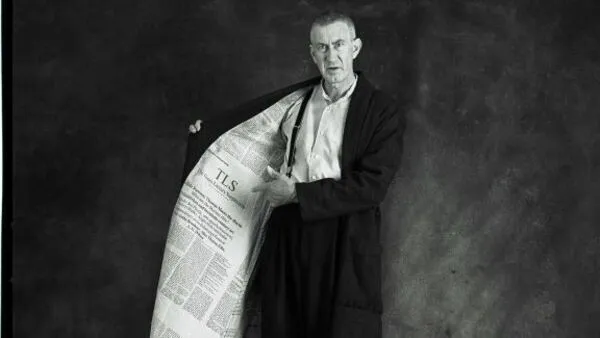

Revely-Calder is right in his diagnosis that there are not enough academic jobs to go around and that ‘publish or perish’ looms over all disciplines. But it is not clear how admonishing young and older critics with the injunction to ‘write better’, or to produce work that accords with one very particular version of literary value, helps us ‘maintain, continue, and repair our “world”’, to use Joan Tronto’s famous definition of care. It feels more like a matter of taste. One person’s high-minded criticism is another person’s rubbish. For Beckett’s Molloy, the Times Literary Supplement was excellent material for lining one’s greatcoat, due to its ‘neverfailing toughness and impermeability. Even farts made no impression on it’. Molloy carefully puts what he designates as rubbish, alongside what he values, to particular uses. The same might be said for those who write about literature, wherever they happen to publish.

The Samuel Beckett Society

Photo: Barry McGovern performing in I’ll Go On